The Rumi Oracle Deck: Persian Miniature Art Meets Sufi Mysticism

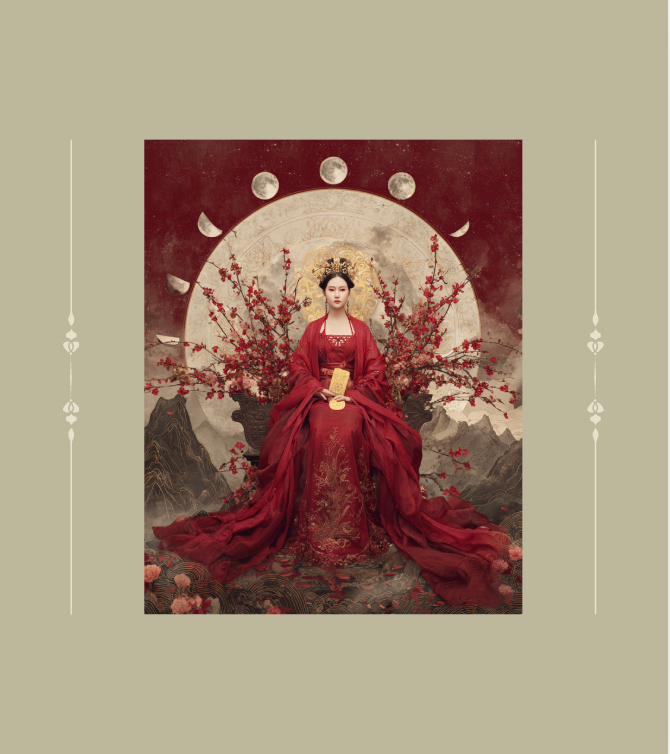

When I set out to create an oracle deck inspired by Rumi's poetry and Sufi mysticism, I knew the visual language had to honor the tradition from which his wisdom emerged. Persian miniature painting - with its jewel-like colors, intricate ornamentation, and symbolic depth - seemed like the natural choice. But the creative process revealed something I hadn't anticipated: the profound philosophical gap between photographic realism and symbolic representation. We've become so conditioned by selfies, Instagram filters, and photographic precision that encountering faces rendered in Persian miniature style can feel jarring at first. Those stylized features aren't a technical limitation - they're a theological choice. Understanding why changed everything about how I approached this deck.

What Are Persian Miniatures?

Persian miniature painting emerged during the Ilkhanid period (13th-14th centuries) and reached extraordinary heights during the Safavid dynasty (16th-17th centuries). These weren't standalone artworks meant for gallery walls - they were manuscript illustrations, created to accompany poetry, historical chronicles, and religious texts. The paintings illuminated stories from Ferdowsi's Shahnameh (Book of Kings), scenes from Nizami's romantic epics, and Rumi's own spiritual poetry.

The technical characteristics are immediately recognizable: brilliant jewel tones achieved through mineral pigments and gold leaf, compositions with flattened perspective rather than Western three-dimensional space, and extensive decorative borders filled with intricate geometric and floral patterns. Figures appear elegant and elongated, their faces rendered in profile with almond-shaped eyes, arched brows, and small mouths. Trees and gardens bloom with stylized flowers that follow symbolic rather than botanical accuracy. Everything feels both luminous and otherworldly.

But these formal qualities aren't arbitrary aesthetic choices - they emerge from a completely different understanding of what art is supposed to accomplish. Western art from the Renaissance onward increasingly prioritized mimesis: the faithful reproduction of observable reality. Persian miniatures operate from another premise entirely: art reveals essential truths that transcend material appearance. The goal isn't to copy what you see with your physical eyes - it's to manifest what can be understood through spiritual insight.

Major centers of Persian miniature production included Herat, Tabriz, and Isfahan, with royal workshops (kitabkhana) employing master painters, calligraphers, and illuminators who collaborated on manuscripts that could take years to complete. The greatest masters - artists like Kamal ud-Din Behzad (c. 1450-1535), Sultan Muhammad (active 1510-1555), and Riza Abbasi (1565-1635) - were celebrated in their time and studied by subsequent generations. Their work wasn't signed in the Western sense, but their distinctive styles were recognized and valued.

Why Faces Don't Look "Real" (And Why That Matters)

This is where I struggled most during the creation process. Every reference image I studied showed those characteristic stylized faces - beautiful, serene, almost mask-like in their uniformity. My Western-trained eye kept wanting more individuality, more psychological specificity, more of what we've learned to call "realistic" portraiture. But that impulse itself revealed my cultural conditioning.

Islamic art developed within theological frameworks that approached representation very differently than Christian European traditions. While there's no absolute prohibition against figurative art in Islam (despite common misconceptions), there is a deep awareness of the dangers of idolatry and the impossibility of truly capturing divine creation. This led to artistic choices that emphasize pattern, geometry, and symbolic rather than literal representation.

In Persian miniatures, faces are deliberately non-individualized because the point isn't psychological portraiture. These paintings don't ask "what does this specific person look like?" but rather "what does this archetypal moment reveal about human experience of the divine?" A king isn't rendered to capture his unique features - he's depicted to embody the essence of just rulership. A lover gazing at the beloved isn't meant to be a specific person you could recognize on the street - it's the universal experience of love-longing made visible.

The stylization serves the work's purpose. These paintings accompanied poetry and mystical texts where the literal surface narrative points toward deeper spiritual truths. Rumi's poetry works exactly this way - the drunk wandering the streets isn't literally intoxicated, he's dissolved in divine love. The beloved with the beautiful face isn't one person, but the presence of God made manifest in all beauty. The visual language needed to match this symbolic density.

Western realism emerging from the Renaissance said: capture what the eye sees with increasing accuracy. Persian miniature tradition said: reveal what the soul knows beyond physical sight. Neither approach is more sophisticated than the other - they're serving different visions of art's purpose.

Sufi Mysticism and the Language of Ornamentation

Sufism - the mystical dimension of Islam - profoundly shaped Persian artistic traditions. Sufi practice centers on the dissolution of the individual ego-self in order to experience union with the Divine. This theological framework naturally informed visual representation.

The elaborate ornamentation in Persian miniatures isn't mere decoration. Those intricate borders, geometric patterns, and endlessly spiraling vines serve a spiritual purpose. They create what Islamic art scholars call "infinite pattern" - designs that could theoretically extend forever, reminding the viewer that material manifestation emerges from and returns to the infinite Divine source. The eye follows these patterns without finding a definitive beginning or end, mirroring the Sufi understanding of reality as continuous divine emanation.

Color carries symbolic weight. Gold represents divine light and spiritual illumination. Deep blue suggests the infinite heavens and transcendent wisdom. Green connects to paradise and renewal. Red embodies earthly passion that must be transformed into spiritual longing. These aren't arbitrary associations - they're part of a symbolic vocabulary developed over centuries of mystical practice and artistic refinement.

The flattened perspective in Persian miniatures also reflects Sufi philosophy. Western perspective with its single vanishing point privileges one viewer's position as central and authoritative. Persian miniatures present multiple viewing angles simultaneously, suggesting that ultimate truth can't be captured from any single position. Reality as understood through Sufi practice isn't fixed and objective but multifaceted, revealing different aspects depending on the viewer's spiritual state.

Gardens appear constantly in these paintings - not realistic gardens but idealized spaces of geometric perfection, flowing water, and eternal spring. These represent both the paradise that awaits believers and the soul's longing for return to its divine source. When lovers meet in gardens or mystics contemplate beneath flowering trees, the setting isn't just backdrop - it's theological statement about where and how the soul encounters divine presence.

Visual Patterns as Consciousness Technology

These infinite patterns aren't merely decorative or symbolic - they function as actual technologies for altering consciousness. When you gaze at a Persian miniature's intricate borders, or contemplate a yantra's nested geometric forms, or follow the spiraling vines that frame a garden scene, something happens in your nervous system. Your breathing naturally begins to slow and deepen. Your scattered attention gathers and focuses. The boundary between observer and observed starts to soften.

This is deliberate design that emerges from centuries of mystical practice. Islamic geometric patterns, whether in tilework, manuscript illumination, or architectural decoration, create visual rhythms that entrain your consciousness. Your eyes follow the repeating forms - triangle to triangle, curve to curve, petal to petal - and that rhythmic movement becomes a form of moving meditation. The patterns lead you inward, deeper and deeper, until you're no longer analyzing what you're seeing but experiencing it directly.

Many practitioners report that after sustained contemplation of these geometric forms, static images begin to appear animated - clouds seem to move, patterns seem to breathe, the entire composition pulses with subtle energy. This isn't hallucination or imagination. It's your consciousness shifting into a receptive state where you perceive the energetic reality beneath material form. The Sufis understood this: beauty arrests the discursive mind so that direct perception can emerge.

This is why oracle work with cards rooted in these traditions can feel different from working with more literal or realistic imagery. You're not just interpreting symbols - you're allowing visual patterns refined over centuries to shift your consciousness into states where intuition speaks more clearly than logic. The ornamentation serves a function: it creates the conditions for insight to arise.

When you pull a card from the Rumi Oracle and find yourself simply gazing at it, lost in the patterns and colors before you even consider its "meaning," that's the design working as intended. The beauty opens you. The patterns quiet your analytical mind. And in that opened, quieted space, the card's wisdom can reach you directly rather than being filtered through conceptual interpretation.

Rumi's Poetry and Visual Language

Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi (1207-1273) was a Persian Sunni Muslim scholar, theologian, and Sufi mystic whose poetry has transcended time, language, and religious boundaries. Born in present-day Afghanistan, Rumi eventually settled in Konya (in present-day Turkey) where his encounter with the wandering dervish Shams-e Tabrizi transformed his life and ignited the ecstatic poetry for which he's remembered.

His Masnavi (or Mathnawi) - often called "the Quran in Persian" - spans six books and over 25,000 verses. His Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi contains thousands of lyric poems. Both works use dense symbolism, paradox, and multi-layered meaning. A poem about a chickpea boiling in a pot becomes a teaching about the soul's refinement through suffering. A story about Moses and a shepherd reveals truths about the inadequacy of formal religious practice divorced from genuine devotion.

Rumi's poetry and Persian miniature painting share fundamental characteristics: both work through symbol rather than literal representation, both embrace beauty as a path to truth, both layer meaning so that surface narrative and deeper significance operate simultaneously. When Rumi writes about wine, taverns, and intoxication, he's not advocating drinking - he's using the metaphor of drunkenness to describe mystical states of consciousness. When miniature painters depict these same tavern scenes, they're visualizing spiritual states, not documenting actual behavior.

This is why Persian miniature style felt essential for a Rumi-inspired oracle deck. His poetry demands a visual language that operates the same way - through symbol, beauty, and layered meaning rather than literal depiction.

Creating the Rumi Oracle Deck: Cultural Translation and Creative Honesty

I need to be clear about my position in this creative process: I'm a Western woman, raised in American culture, trained in Western art history and psychology. No matter how deeply I studied Persian miniature painting, Sufi philosophy, and Rumi's poetry, I was always looking through a cultural lens shaped by my own formation. The deck I created is inevitably a reflection of my understanding - not an authentic reproduction of Persian tradition, but a Western practitioner's reverent interpretation.

This matters because cultural appropriation happens when we extract aesthetic elements from other traditions while ignoring or distorting their meaning, usually for profit. What I aimed for instead was cultural appreciation and bridge-building - learning from these traditions with respect, acknowledging my limitations, and being honest about what this deck is and isn't.

The Rumi Oracle isn't Persian miniature art. It's oracle cards inspired by Persian miniature tradition, created for the specific function of divination and personal spiritual reflection. And that functional difference required adaptations.

Oracle cards serve a different purpose than manuscript illuminations. They're not accompanying text that provides context and narrative. They're pulled individually, contemplated in silence, and expected to speak directly to the person holding them. This requires immediate emotional resonance - something that can catch your breath and open a door to insight within seconds of seeing it.

This is why I made the choice to include faces - and not just stylized profile faces in traditional Persian miniature style, but faces that show wonder, awe, contemplation, and encounter with the divine. I wanted people using this deck to see themselves reflected in those moments of spiritual experience. I wanted faces that invite identification: "That could be me, in that garden, receiving that revelation. That longing, that surrender, that transformation - I've felt that."

This was a conscious adaptation based on what oracle work requires. Traditional Persian miniatures served their purposes perfectly within their cultural and functional context. But an oracle deck needs to function as a mirror - something that reflects the user's soul back to them in ways that illuminate and guide. Those faces filled with wonder became essential to that mirroring function.

I also made choices about color saturation, composition, and symbolic elements based on what would read clearly in a small card format. Manuscript miniatures were often quite small themselves, but they were viewed in books, surrounded by calligraphy and decorative borders, studied at leisure. Oracle cards get shuffled, spread on tables, photographed, and contemplated in brief moments. They needed visual impact and clarity that could work within those constraints.

Throughout the creation process, I tried to stay aware of when my Western perspective was shaping choices. I studied extensively - reading Sufi philosophy, examining museum collections of Persian miniatures, consulting with people who had deeper cultural knowledge than I did. But I also accepted that I couldn't transcend my own cultural position. The deck carries my soul's resonance with this tradition - the aspects that moved me, spoke to me, and felt aligned with Rumi's universal mysticism.

What I hope I've created is something honest: not a fake Persian artifact, but a Western practitioner's sincere offering, inspired by profound traditions I respect and continue learning from. If I've made mistakes - and I surely have - I remain open to learning and doing better. The deck is my interpretation, offered with humility, not a claim to authority I don't possess.

Oracle Work Across Cultures

One of Rumi's most remarkable qualities is how his mysticism transcends the specific religious and cultural context from which it emerged. His poetry speaks to Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists, and secular seekers alike - not because it's vague or universalist, but because it touches archetypal human experiences of longing, surrender, transformation, and union with something larger than the isolated self.

This is what makes Rumi's work so powerful as a foundation for oracle practice. Oracle decks at their finest serve as mirrors - they reflect aspects of the user's soul back to them in ways that illuminate, challenge, and guide. The Rumi Oracle attempts to hold that mirror using visual language inspired by the tradition that shaped Rumi's world, adapted for contemporary practice.

People across the world are drawn to these cards - not because they're Persian or because users necessarily identify as Sufi, but because the archetypal themes Rumi explored are genuinely universal. The beloved whose face appears in all beauty. The longing that drives us toward wholeness. The necessity of surrendering ego-control to experience grace. The refinement that comes through difficulty. These truths don't belong to any single culture - they appear in mystical traditions worldwide.

What Persian miniature tradition offers is a specific visual vocabulary for making these invisible realities visible. The gardens, the lovers, the color symbolism, the infinite patterns - these become a language through which divine mystery can be contemplated without being reduced to literal dogma.

When someone in Brazil or Singapore or Mississippi pulls a card from this deck and experiences a moment of recognition - "yes, this speaks to what I'm experiencing" - that's not cultural appropriation. That's the universal dimension of mystical wisdom making itself accessible through beauty and symbol.

My role as creator was to build a bridge - honoring the Persian artistic tradition that gave these visual forms their richness while making them accessible for contemporary oracle practice across cultures. Not erasing their origins or pretending they're culturally neutral, but acknowledging their roots while recognizing that the mystical truths they point toward belong to all of humanity.

Art as Spiritual Practice

Creating this deck taught me something I hadn't fully understood before: in the Persian miniature tradition, the process of making art was itself a spiritual practice. Master painters often meditated before beginning work. They approached their craft with the same devotion a Sufi practitioner brings to dhikr (remembrance of God). The painstaking attention to detail, the grinding of pigments, the precision of brushwork - these weren't mere technical requirements but acts of worship.

This contrasts sharply with contemporary Western approaches to art-making that often prioritize individual expression, innovation, and breaking with tradition. Persian miniature painters worked within established forms, studying masters who came before, refining techniques that had been developed over generations. The goal wasn't radical originality but achieving such mastery that beauty itself could shine through the work.

Working with AI art generation to create these oracle cards obviously differs radically from the traditional methods. I'm not grinding lapis lazuli for blue pigment or applying gold leaf with a steady hand. But I tried to bring the same quality of devotional attention to the process - refining prompts until the images captured the spiritual essence I was seeking, adjusting colors until they sang with the right symbolic resonance, choosing compositions that honored the tradition while serving oracle functionality.

The technology is entirely contemporary, but the intention connects back to those medieval workshops: creating beauty that serves spiritual awakening rather than ego aggrandizement. Using art to point toward truths that transcend the material while honoring the beauty of material creation as divine gift.

An Invitation to Study Both Traditions

If you're drawn to the Rumi Oracle deck, I encourage you to explore the artistic and mystical traditions that inspired it. Persian miniature painting rewards deep study - the more you understand about the symbolic systems, historical context, and spiritual foundations, the more layers of meaning reveal themselves.

Major museum collections worth exploring include the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Islamic Art galleries, which house extraordinary examples of Persian manuscripts and miniatures. The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian have exceptional Persian painting collections available through virtual tours. The British Museum and British Library hold significant Persian manuscripts. For those who can travel, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul offer immersive encounters with this tradition.

For Rumi's poetry itself, Coleman Barks' translations have made him accessible to English-speaking audiences, though it's worth knowing that Barks translated from existing English translations rather than the original Persian, and his versions tend toward New Age sensibilities that smooth over some of Rumi's theological complexity. For translations closer to the original, seek out Jawid Mojaddedi's scholarly translation of the Masnavi or works by A.J. Arberry.

Learning about Sufism as a living spiritual tradition (not just aesthetic inspiration) means engaging with scholars like Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Annemarie Schimmel, and William Chittick who've written extensively about Islamic mysticism with both academic rigor and spiritual sensitivity.

The Rumi Oracle exists as one small bridge between these profound traditions and contemporary spiritual practice. It's not the tradition itself - it's an invitation to explore further, to learn more deeply, and to let these ancient wisdoms speak to your contemporary life.

Beauty as Path to Truth

What ultimately drew me to Persian miniature painting as the visual language for this oracle deck was something central to both Sufi mysticism and Islamic aesthetics: the understanding that beauty is not frivolous decoration but a path to truth. In Sufi thought, all beauty in the material world reflects divine beauty. When we encounter something beautiful - whether art, nature, or another human being - and feel our hearts open, we're experiencing a moment of connection to the source of all beauty.

This is why Persian miniatures lavish such attention on visual beauty. Those jewel colors, that intricate ornamentation, those idealized gardens - they're not escapes from reality but windows into deeper reality. They remind us that the divine manifests everywhere, that the material world isn't separate from spiritual truth but shot through with it.

Oracle work operates from similar premises. We use beautiful objects - cards with compelling imagery - to access insight that exists beyond words and logic. The beauty isn't manipulation or marketing - it's the medium through which intuition and wisdom can speak. When you pull a card and feel something shift in your chest, when an image resonates before you can articulate why, when the beauty of what you're seeing opens you to hearing what you need to hear - that's beauty doing its essential work.

The Rumi Oracle attempts to honor this understanding. Each card was created with devotion to beauty not for its own sake but as a doorway. The colors, compositions, and symbolic elements all serve the function of opening that door between your conscious mind and the deeper wisdom already present in your soul.

This deck exists because Rumi's poetry opened doors for me - into joy, grief, surrender, and the strange comfort of knowing that longing itself is prayer. Creating visual expressions of his mystical vision became my way of saying thank you to a tradition that has given me so much. If these cards open similar doors for others, that's grace - the gift given becomes gift shared.

Explore our complete guide to Oracle types.

Explore our oracle cards hub for in-depth coverage of animal, astrological, literary, goddess, and nature oracle systems.

Stop Googling Card Meanings - Start Reading with Confidence

Get my beginner-friendly $22 course and learn to trust your intuition instead of memorizing meanings. Practice with simple spreads and build confidence without constantly looking things up